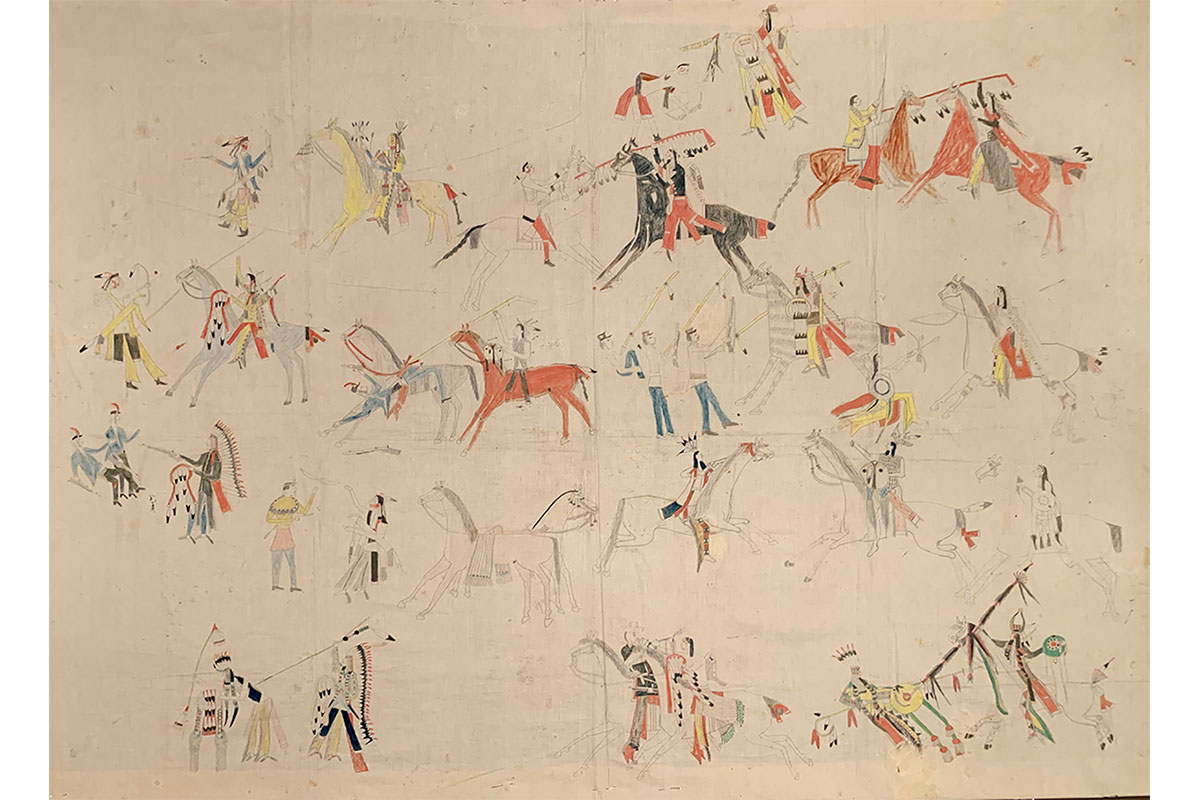

Pictorial muslin

Central Plains

ca. 1870-1890

paint on muslin

height: 67"

width: 82"

Inventory # P4357

Sold

PROVENANCE

Collected by Lewis Newton Hornbeck (b. 1849), an employee of the U.S. Government Indian Service between 1880-1890, residing in the area of Anadarko and Minco, OK

By descent through the family to William Sonnamaker, Hobbs, NM

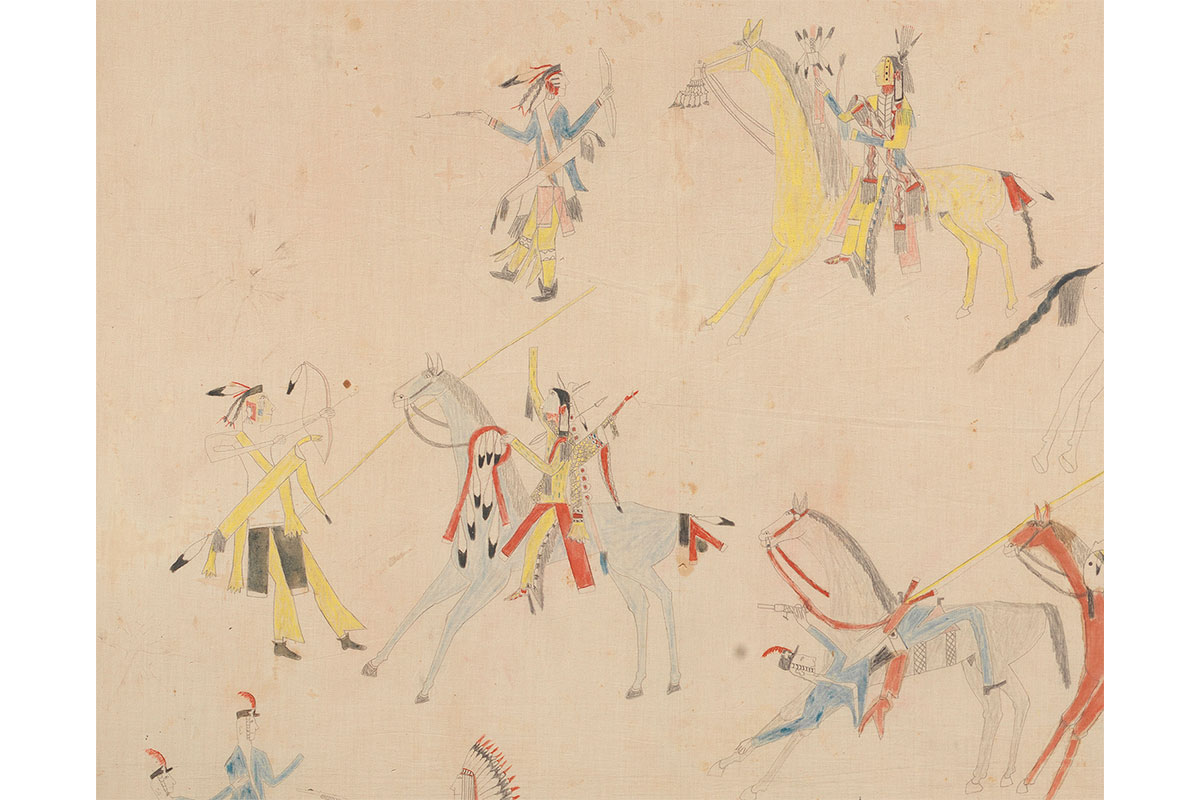

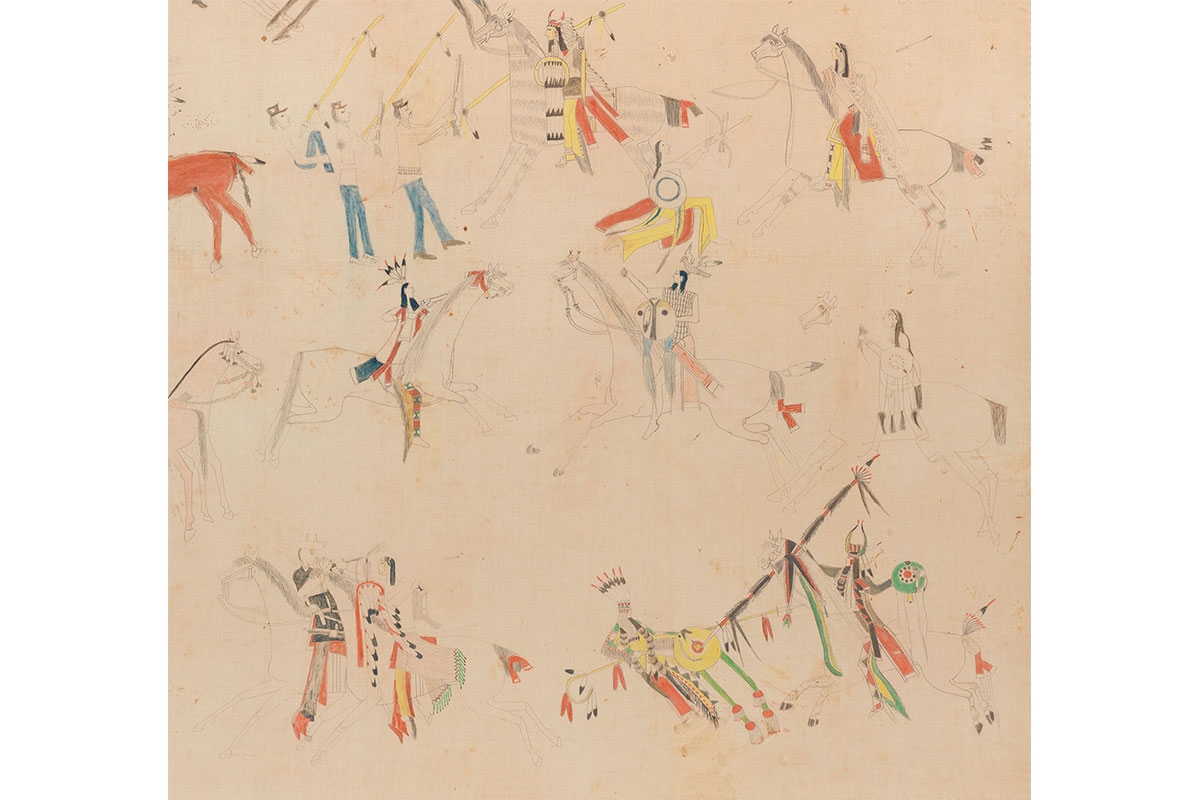

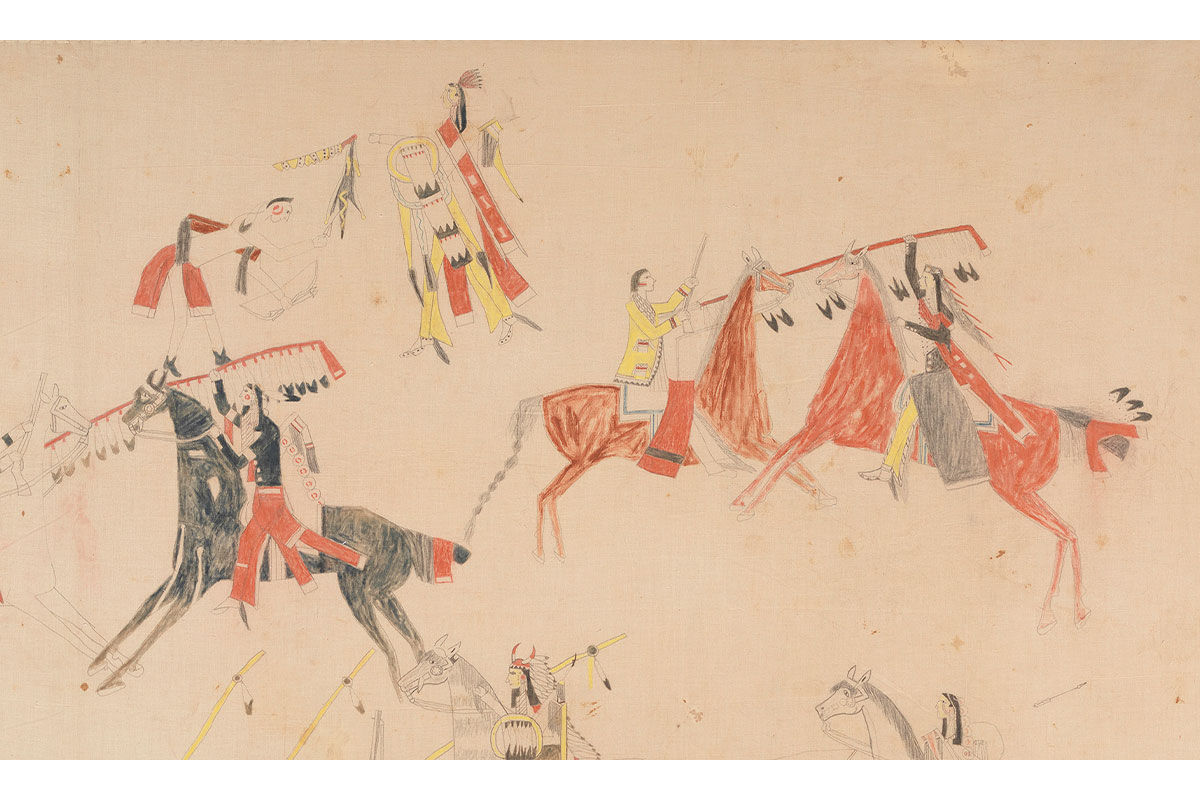

This exceptional painted muslin provides a rare graphic depiction of Native American warriors fatally engaging with US soldiers in the reservation period post-1870. Painting on panels of muslin or canvas cloth developed in the 1880s, having evolved from pictographically painted tipi liners. A tipi liner was an ingenious architecture element that was fixed to the lower section of the interior of a tipi and acted as a device to move smoke along the inside wall to escape through the hole at the top. During the reservation period, most Native American families were moved from their traditional tipis into log cabins. The mud and moss chinking between the logs frequently dried out, creating drafts. To combat this problem, panels of cloth were often fixed around the interior. Male warrior artists on the Great Plains traditionally painted personal histories and “war records” on buffalo hides and war shirts. With the decimation of the buffalo herds, the pressure of Euro-American military expansion and colonial settlement in the mid to late 19th century, painting on hide declined. This change was accompanied by the increasing availability of new materials through trade on the Plains. Paper obtained from ledger books and commercially traded muslin cloth gradually replaced hide as mediums of narrative expression. Similar in purpose and appearance to earlier hide linings used in tipis, the cloth cabin liners were painted with depictions of the owner's battle exploits. In the early-1890s ethnologists working on reservations frequently acquired these cabin liners for museums. Recognising the economic potential of their work, artists soon took up commercial production of these remarkable historical records.