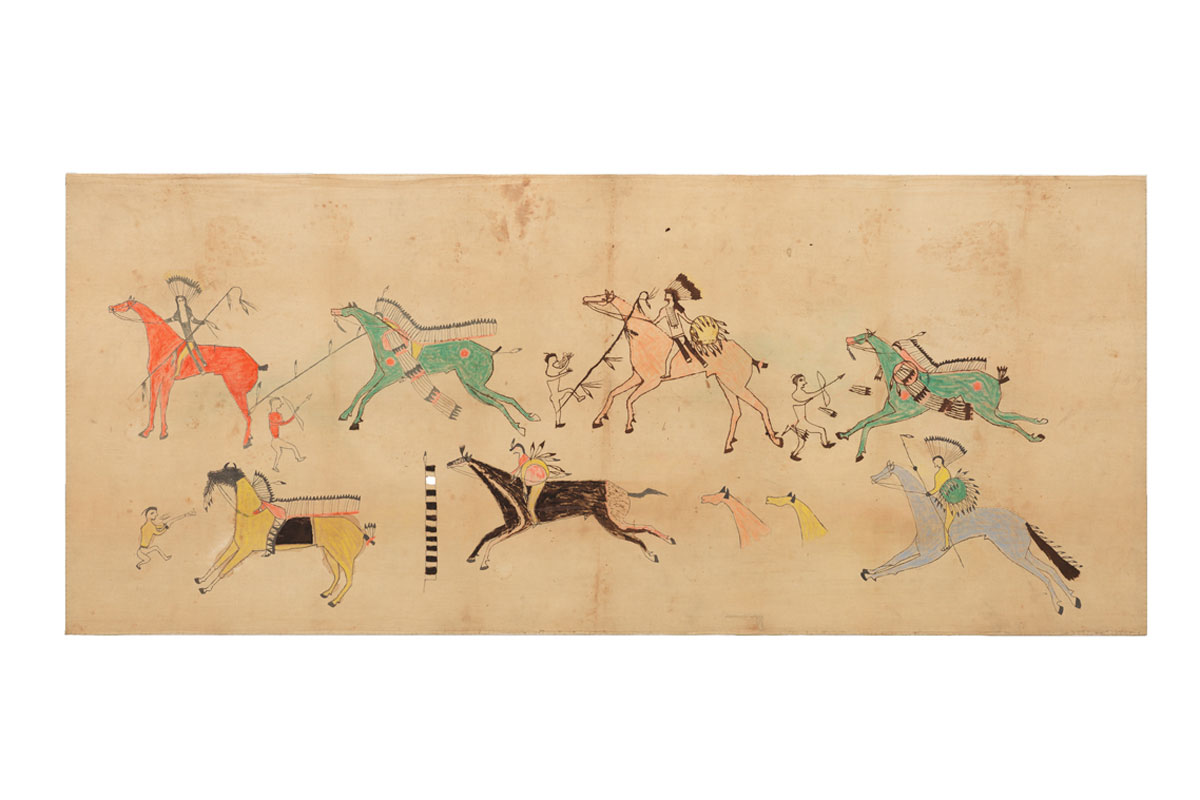

PICTOGRAPHIC MUSLIN

Lakota

Northern Plains

ca. 1900-1910

muslin, paint

length: 77”

width: 32”

Inventory # P4070

Sold

acquired by The Museum of Fine Art, Houston, TX

Provenance

Collected by Isabella Jean Macroy (b. 1860 d. 1947) a schoolteacher in the Dakota and Oklahoma territories.

A Lakota Painted-Muslin Panel, ca. 1890.

Lakota paintings on panels of muslin or canvas cloth developed in the 1880s, when Indian families were moved from their traditional tipis into log cabins. The mud and moss chinking between the logs quickly dried out, when chunks might fall out of position, creating drafts. To combat this problem, panels of cloth were often tacked up around the interior. As these were similar in both purpose and appearance to the earlier, leather linings used in tipis, the cloth cabin liners were often painted in similar fashion, with depictions of the owner's battle exploits.

These attractive cabin liners quickly found an economic market as "Indian curios." When that happened, by the early-1890s, various Indian artists began to paint panels of cloth specifically for sale to tourists, or government officials. This painting is an example of that progression. If it had been created for home use as a cabin liner, there would be tack or nail holes around the perimeter. Lacking these, we recognize an early example of Lakota, male "commercial ingenuity." Prevented from supporting his family by hunting, this husband and father had turned his hand to another means of earning a small income.

This artist was either an Oglala from Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota, or a Sicangu (Brule), from Rosebud Reservation. In the quarter century, 1850-1875, during which the events depicted had occurred, one of the primary enemy tribes opposed to Oglala & Sicangu expansion was the Pawnee, located south of Lakota territory in present Nebraska . All four of the pedestrian enemies depicted are Pawnee, recognizable from their plucked hairstyle, with only one or two, narrow scalplocks; and especially, black-dyed moccasins with high ankle flaps. These are worn by the two enemy figures at top, right and center. Both Pawnee also appear to be naked, a common battle choice (see, for example, Dodge, 1882: 457). The other, two Pawnee are shown as bare-footed, wearing only cloth shirts.

A fascinating feature of this painting is the clear intention to depict sound: the lines emanating from the mouths of two of the Pawnee are meant to show that they were either singing protective war songs, or more probably hurling insults at the Lakota, as they were ridden down.

During a stand-off encounter with Lakota in 1867, Col. Richard I. Dodge was supported by a Pawnee hunting companion. The colonel and his partner had superior firearms and a strong position, so after four hours of stratagems and aborted attacks, a Lakota war party of fifty men gave up and left them unmolested.

During all the charges the Pawnee had evinced the greatest eagerness for fight...Answering yell for yell, he heaped upon them all the opprobious epithets he could think of in English, Spanish, Sioux and Pawnee, When they wheeled and went off the last time, he turned to me with the most intense disgust and contempt, and said emphatically, "Dam coward Sioux!" (Dodge, 1882:458).

This Lakota artist has documented, in graphic form, Pawnee battle insults similar to those described by Col. Dodge.

Three types of distinctively-decorated battle lances, indicative of membership in various warrior societies, are illustrated on this panel. The best, visual reference that assists in distinguishing these is Bad Heart Bull, 1967: 104-116. Crooked lances, with the upper end bent like a shepherd's crook, the shaft wrapped with strips of dark otterskin and hung at intervals with golden eagle feathers, were used as insignia by three of the Lakota warrior societies: the Wiciska (Horned White Headdresses); the Ihoka (or Iroka, meaning Badger); and the Sotka Yuha. The latter name "is said to imply a smooth, unadorned stick; hence, they have empty [bare] lances, referring to the custom of investing certain members with plain lances to which they may tie feathers if coups are counted" (Wissler, 1912: 33).

Three of these "straight lances" are depicted on the panel, showing a progression of accomplishment. A "bare lance," definitive for the Sotka Yuha, is carried by the rider at lower right. The rider in the top row, second from left, on a blue roan painted with a red muzzle and red circles on the shoulders and hips, carries a similar lance now wrapped with otterskin and hung with single eagle feathers symbolizing war deeds. The same man on a later occasion, on the same horse and displaying the same headdress and shield, is shown in the top row, far right. His lance is now hung with additional eagle feathers to document further accomplishments. This man was probably the artist, and he was a lance bearer of the Sotka Yuha Warrior Society. The crooked lances depicted were probably also Sotka Yuha regalia, carried by war partners of the same organization (compare Bad Heart Bull, 1967: 108). It is likely these men were brothers or cousins of the artist.

Remarkably, two horse masks, rare examples of Plains Indian battle accoutrement, are also depicted on this muslin panel. At bottom left, a brindle buckskin gelding is protected with an intimidating mask that represents an Underworld Bull, a nightmare creature like a huge buffalo described in ancient myths, which brought earthquake and crushing death (see Cowdrey, Martin & Martin, 2006: 12-16, & especially, Fig. 2.14a). Note the brown over-painting of the buckskin coat which nicely represents the rare, brindle markings. In the earthquake context of the mask, the unusual coat markings of the horse, which the artist has taken such trouble to convey, might well be intended to invoke a blinding duststorm.

A second, smaller mask distinguishes the black gelding following the buckskin. The wrapped forelock of the rider indicates he is a man who had received a protective vision from the God of Thunder, Lakota avatar of War. The wrapped forelock of the horse makes this connection explicit. The dark steed is painted with red lightning strikes down the legs, and a white rump speckled with black dots that represent a storm of hail. As the horse charges, it symbolizes an engulfing thunderstorm, the hooves striking as bolts of electricity and trampling the enemy like a deluge of hail stones. A third style of lance, with a checkered banner attached along the shaft, consisting of black and white feathers, belongs to the rider of the black horse. This is an insignia of the Cante T'inza (Strong Heart) Warrior Society (Bad Heart Bull, 1967: 104).

The two, horse heads at lower right are "shorthand" symbols for Pawnee animals captured during the action depicted.

Mike Cowdrey

San Luis Obispo, California

12 January 2014

Bibliography

Bad Heart Bull, Amos (Helen H. Blish, ed.)

1967 A Pictographic History of the Oglala Sioux. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Cowdrey, Mike, and Ned Martin & Jody Martin

2006 American Indian Horse Masks. Nicasio, CA: Hawk Hill Press.

Dodge, Col. Richard Irving

1882 Our Wild Indians: Thirty-three Years' Personal Experience Among the Red Men of the Great West. Hartford, CN: A.D. Worthington & Co.

Wissler, Clark

1912 "Societies and Ceremonial Associations in the Oglala Division of the Teton Dakota."

Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. 11.

Download essay (.PDF 102 KB)