August 7 – September 29, 2022

Fast Ponies: Past to Present

The Armory Show 2022

Donald Ellis Gallery is pleased to announce its participation in The Armory Show 2022, held at the Javits Center in New York September 9-11, with an invitation-only preview on September 8.

The gallery will present Fast Ponies: Past and Present, placing early 20th century Plains pictographic drawings in dialogue with photographic work by critically acclaimed Lakota artist and filmmaker Dana Claxton.

Plains pictographic drawings were predominantly created by male warrior-artists as a means of recording personal and collective histories. Produced at a time of increasing American imperial expansion on the Great Plains, Ledger Drawings speak to Plains warrior culture and the importance of the horse to it.

Dana Claxton’s photographic work resonates with the pictorial conventions of Plains pictographic drawing. By staging the human figure in a vast open space her images foreground the dress and personal belongings worn by fellow artist and filmmaker Iikaakskitowa (Cowboy Smithx). Like the warriors recorded in historical Plains drawings, Claxton’s photographs project Indigenous male identities in ways that defy stereotypical representations, influenced at once by Plains warrior culture, Hip Hop, lowriding and traditional applied aesthetics.

The exhibition is a continuation of Fast Ponies and War Bonnets: A Lakota Look at Ledger Art, an online exhibition previously curated by Ms. Claxton.

"I attempt to create infinity and a large Great Plains landscape, thus invoking that magical place where sky meets land and the above and below converge."

Dana Claxton

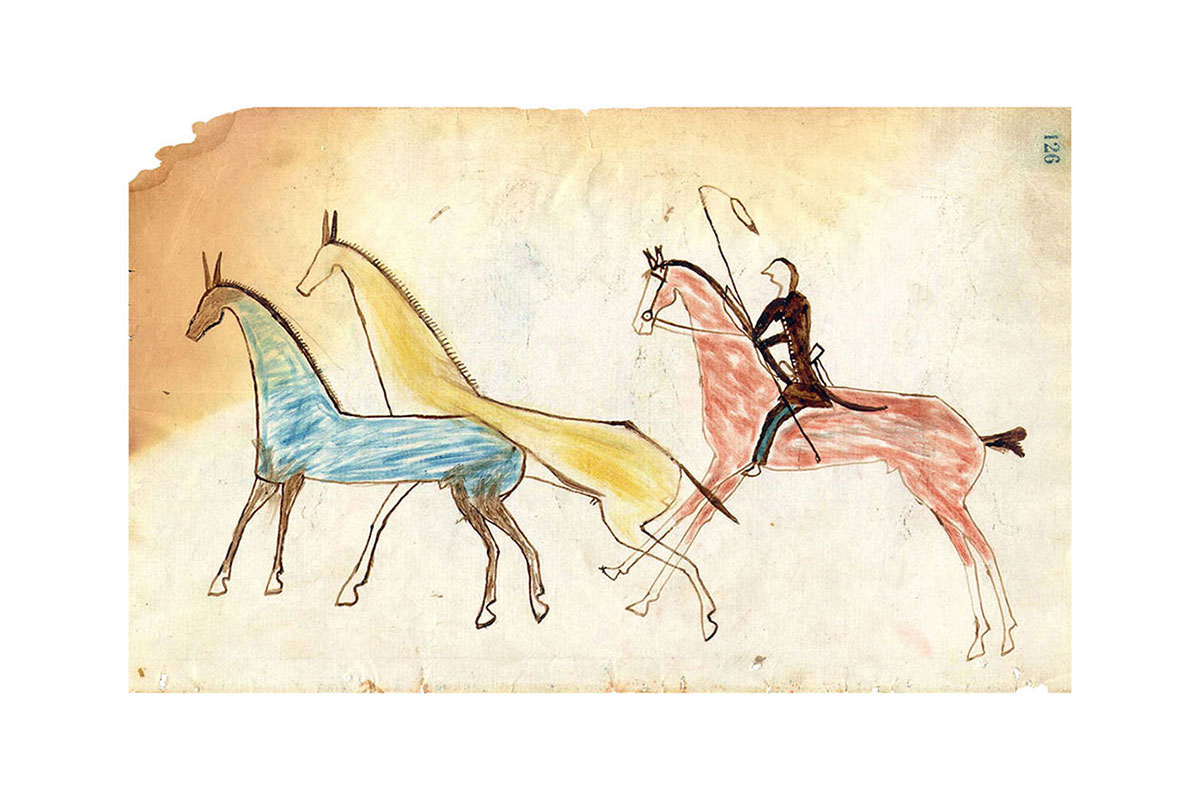

Ledger Drawing

attributed to Cedar TreeCedar Tree Ledger Book (pg.71)

Southern Arapaho

Central Plains

Both Ledger Art and Claxton’s photographic work foreground the visual expression of predominantly male identities. By placing the human figure in an open space pictorial detail is reserved for personal belongings. The elaborately painted shield, beaded blanket strip, face and body painting, long eagle feather war bonnet and lance tipped with red horsehair depicted on page 71 of the Cedar Tree Ledger Book, for example, identify the warrior’s status and rank within a given society and signify past achievements in battle. Great care is also taken in the representation of the horse, considered sacred by many Plains cultures, while individual anatomic features are rendered only schematically. Claxton’s firebox Easy Rider NDN also draws from various contemporary male identities. Claxton replaces the horse with a low-rider bicycle, evoking simultaneously the mobility central to Plains life and, according to the artist, “that classical desire to be free on the highway.” A single male figure is wearing an elaborately beaded cowboy hat and chaps alongside a fringed jacket, recalling American cowboy culture and lowriding, popular among men in more urban settings. The playful inclusion of a bow and arrow as well as a beaded hand-held axe relates him to some of the warriors depicted in Ledger Art.

"I have an interest in the theatrical and blending realms and periodization, as a way to connect the past, the now and the future and all within the spiritual belief of Mitakuye Oyasin – everything is related and a deep belief of Lakota worldview."

Dana Claxton

Ledger Drawing

attributed to Wanbli Hito (Roan Eagle), b.1863Roan Eagle Ledger Book (pg. 59)

Lakota

Northern Plains

Ledger Drawing

attributed to Wanbli Hito (Roan Eagle), b.1863Roan Eagle Ledger Book (pg. 155)

Lakota

Northern Plains

Like the warriors in Ledger Art, Claxton’s figures perform their contemporaneity, clad in attire that is at once modern and deeply rooted in applied cultural and spiritual aesthetics. Many Ledger Drawings feature Euro-American rifles, Mexican serapes or elements of U.S. military uniforms. In Claxton’s Hip Hop NDN, the cliched distinction between “Cowboys and Indians” is collapsed by way of Iikaakskitowa’s skilful handling of the lasso. His aviator sun glasses, yellow velour tracksuit, cap, gold chains and beaded medallions further reference Native American Hip Hop (NAHH) culture, a widely popular genre speaking to Native experiences on reservations and in urban environments. In Claxton’s own words, “the contemporaneity and futurity of the figure in these works suggest a continuation of tribal autonomy, and aesthetics.” Like Ledger Art, they defy stereotypical representations of Native American cultures as stagnant and outside of time. Instead, past, present and future fold into one another, speaking of the encounters, exchanges and violent conflicts that continue to shape North American Indigenous experiences to the present day.

Not much is known about Cedar Tree, the Southern Arapaho warrior artist to whom these drawings are attributed. Around 1882, the year the Cedar Tree Ledger Book was first collected, he likely resided nearby the Cheyenne and Arapaho Agency in Darlington, Oklahoma. Cedar Tree’s autobiographical drawings describe a man of great accomplishment who possessed an extraordinary visual memory and demonstrated a remarkable attention to detail. Contrary to the conventions of Ledger Art and most Plains pictographic traditions where we see the action in motion from right to left, Cedar Tree’s figures are staged moving from the left hand side of the page to the right. This, as well as the frequent depiction of himself holding a lance in his left hand, suggests that the artist was left-handed.

Ledger Drawing

attributed to Cedar TreeCedar Tree Ledger Book (pg.17)

Southern Arapaho

Central Plains

Ledger Drawing

attributed to Cedar TreeCedar Tree Ledger Book (pg.63)

Southern Arapaho

Central Plains

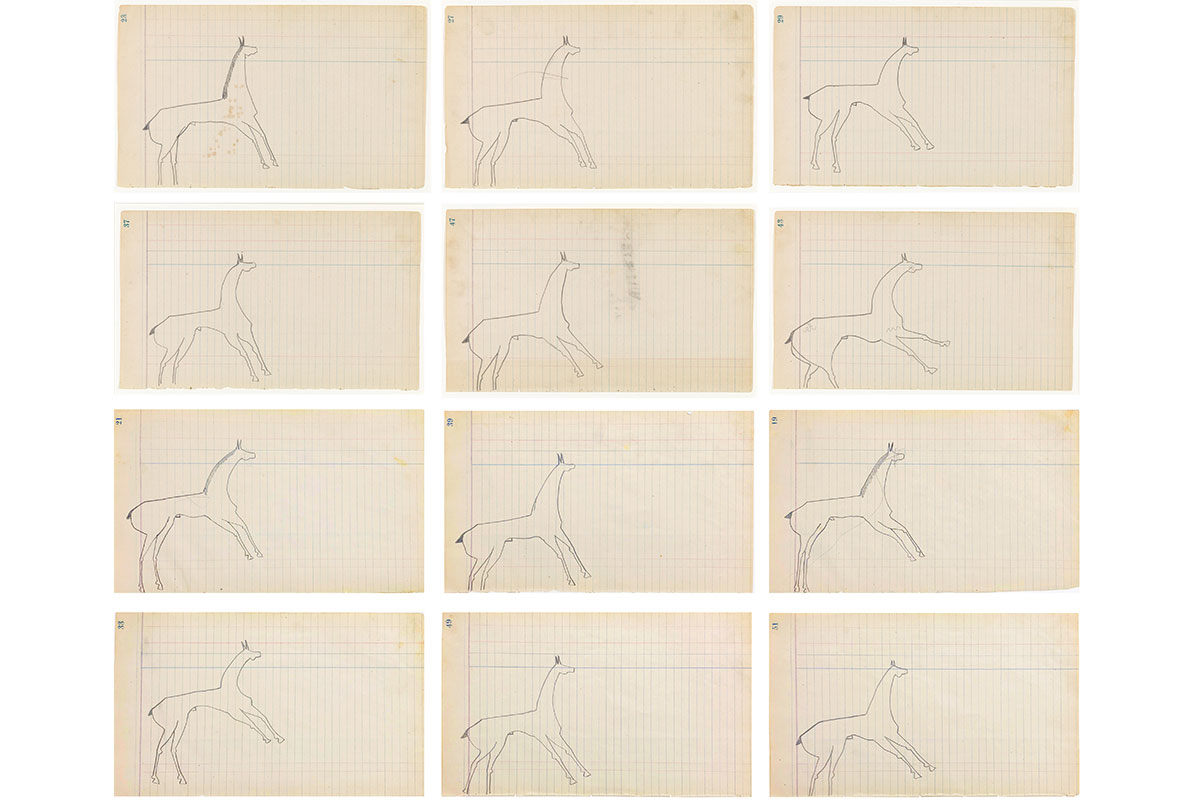

A number of drawings in the exhibition show a single horse silhouette placed against the lined accounting paper on which they were created. These compositions are likely preliminary depictions of one of the recurring motifs of the Ledger Book. The drawings demonstrate the exceptional fluidity with which Cedar Tree was able to capture the powerful presence of the horse. Drawn in a single sweeping motion, the images exhibit not only remarkable understanding of anatomic detail but are imbued with the power of movement. Exemplifying Cedar Tree’s distinct artistic vision, the drawings capture the nobility and courage of the horse, revered for its agility and strength in battle.

Ledger Drawing

attributed to Cedar TreeCedar Tree Ledger Book (pg.29)

Southern Cheyenne

Central Plains

Ledger Drawing

attributed to Cedar TreeCedar Tree Ledger Book (pg.23)

Southern Arapaho

Central Plains

"Easy Rider NDN, that classical desire to be free on the highway, All Warriored Up to be ready to protect your family, land and inherent rights, and Hip Hop NDN dances us into the future with beats while maintaining a connection to the past."

Dana Claxton

Ledger Drawing

attributed to Ma Nim Ick (Minimic or Eagle Head, d.1881)Vincent Price Ledger Book (pg.70)

Cheyenne

Central Plains

This group of drawings from the Vincent Price Ledger Book dates back to the earliest pre-reservation phase of Plains Ledger Art. The book was named after the American actor Vincent Price, who acquired this rare collection of eighty-six Ledger Drawings in the early 1950s. The drawings in the Vincent Price Ledger Book date from about 1875 to 1878, the period immediately following the Indian Wars, and primarily depict the war exploits of Cheyenne warriors during that time of intense conflicts with the U.S. Cavalry. The name glyphs present in the book tentatively identify known Cheyenne warriors such as Jumping Rabbit, Two Crows, Black Horse, Starving Elk and Ma Nim Ick (Eagle Head), the father of Ho Na Nist To (Howling Wolf), one of the most accomplished Ledger artists of the period.

Pictographic painted panels on muslin or canvas evolved from an earlier tradition of painted hide tipi liners, an ingenious architectural device attached to the lower interior of a tipi to guide smoke along the inside wall and through the smoke hole at the top. The appearance of painted muslins in the late 19th century coincides with the forced relocation of Native American families and communities into log cabins on reservations. Artists cleverly adopted the earlier pictographic tradition of the tipi liner, utilising newly available materials such as muslin and coloured ink to create large-scale paintings to be fixed around the interior of their cabins. In later years, cloth cabin liners were frequently commissioned or sold to U.S. military personal, anthropologists and tourists.

In contrast to tipi liners, most of which are painted with abstract geometric designs, pictorial muslins frequently depict the exploits of one or a number of protagonists, referencing events recognised as important by the community. As such, pictographic muslins serve as mnemonic devices of personal and collective histories similar to winter counts and Ledger Art. The extraordinary muslin illustrated here is unusual in the sheer number of scenes depicted, each vignette accompanied by handwritten inscriptions in Lakota. According to Christina Burke, curator of Native American art at the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma, some of the protagonists can be identified as Mato Luta (Red Bear), Mehaka Ciqala (Little Elk), Mato Nape Ska (White Paw Bear) and Kangi Ohitika (Brave Crow). These men appear on the 1885 ration rolls for the Standing Rock Reservation, strengthening the attribution of this muslin to a Hunkpapa Lakota artist.

The quality of each pictorial element is superb, the figures all confidently rendered. Many scenes capture horse raids and battles with Apsáalooke warriors. The richness of detail is notable, including the careful presentation of protective images such as spirit animals or the celestial constellations on various shields, among the most prized possessions of a Plains warrior in the 19th century. Similarly noteworthy is the variety of body poses, ranging from warriors charging at enemies to those ducking away or spread on the ground in defeat. This muslin was clearly painted by a high-ranking artist, capturing the exploits of many of his peers with exceptional virtuosity.

Ledger Drawing

attributed to Mad BullMad Bull Ledger Book (pg.8)

Southern Arapaho

Central Plains

Ledger Drawing

attributed to Mad BullMad Bull Ledger Book (pgs. 105/106)

Southern Cheyenne

Central Plains

"Wopila – giving of thanks. Pilamaya – you have honoured me – by looking and reading about this art work, which is telling a story from right now, from long ago and from the future."

Dana Claxton