Our Ancestors Were Great Hunters Degikup LK43

Louisa Keyser (Dat So La Lee), 1850-1925Southern Washoe

Nevada

April 24 – May 30, 2022

Donald Ellis Gallery is pleased to announce its participation in the 2022 edition of TEFAF New York Spring at the Park Avenue Armory, May 6-10, with an invitation-only preview May 5.

The gallery is presenting a fine selection of historical First Nations art from Canada and the United States. Highlights include a highly important degikup basket by Washoe artist Louisa Keyser (Dat So La Lee, 1829–1925), celebrated as the most accomplished Indigenous basketmaker of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Remarkable for its artistic innovation and technical virtuosity, this outstanding work is one of only a handful of baskets of this scale and importance for sale in the last half-century. The gallery will also present an exceptionally rare Oystercatcher rattle attributed the 18th century Tlingit artist Kadjisdu.acxh II, described as ‘the greatest carver of wood in the history of the Tlingit people’, a selection of Hopi and Zuni katsina dolls, an exceptional Yup’ik mask formerly in the collection of the Surrealist artist Roberto Matta and an important group of pre-historic Inuit ivories.

Louisa Keyser, also known as Dat So La Lee (1850–1925), is celebrated today as one of the most accomplished artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Distinguished by her exceptional craftsmanship, Keyser pushed the techniques, forms and relatively plain surface designs of Washoe basketry to create impressive visually-driven works for sale on the art market. From 1895 to 1925 she worked under the patronage of Abe and Amy Cohn, owners of the Emporium Company in Carson City, Nevada. It was during this period that Keyser developed the "degikup style" she is most famous for; large spherical baskets formed on a broad flat base.

A distinctly modern weaver, the present coiled basket epitomizes Keyser's unrivaled artistic innovation, expanding out into the maximum circumference before tapering to a narrow opening at the top. Variations of her distinctive flame motifs in red and black are arranged in vertical columns across the entire surface of the basket. The technical superiority of her weaving, averaging 30 stitches to an inch, allows for an even spacing and exact alignment of individual units, setting her work apart from that of all other Washoe basket-makers. The resulting visual effect is of exceptionally refined elegance.

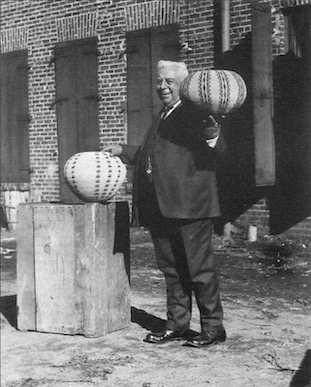

Louisa Keyser with two of her degikup baskets

Abe Cohn stands outside of his Emporium Company in 1924 presenting basket LK43

Propelled by the Arts and Crafts movement of the early 20th century, Keyser's baskets were already highly sought after during her working career. The Cohn's took great care to document each basket individually, issuing certificates of authenticity that helped create a sizeable field of collectors. The present basket is listed as LK43 in the Emporium Company archives and is entitled "Our Ancestors Were Great Hunters". It was Amy Cohn who created names for the artist’s baskets and the many stories relating to Keyser and her innovative designs. An early photograph shows Abe Cohn holding basket LK43, as if presenting it before the camera. Listed at $5,000 in the company ledger, LK43 commanded a sum previously unheard-of for the work of a Native American artist.

This outstanding work is one of only a handful of baskets of this scale and importance for sale in the last half-century. Two of the other baskets, featuring a more common "scatter design", are now in the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and the Eugene and Clare Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown. A third basket was sold by this gallery in 2008 and is now in an American private collection.

Very few names of Northwest Coast artists active in North America during the late 18th century were ever recorded in the literature or oral histories. Among the Tlingit, Kadjisdu.axch II is remembered as “the greatest carver of wood in the history of the Tlingit people.”

This rattle, employed by a shaman to aid in the spiritual work of healing and divination, is among the artist’s most significant known works. The images and types of activity depicted are unlike any other rattle of its type; a unique vision of anthropomorphic figures composed on the back of an elegantly poised oystercatcher with an ivory beak. A striking and unusual feature of this rattle is the near-total asymmetry of the carved imagery. It’s probable that the bear, eagle, wolf, humans, and bear cub are all representations of spirit beings that were helpers to the shaman, drawn from specific visions experienced by him in trance states that were communicated to the carver for him to manifest in wood.

Charms and amulets exhibit perhaps the greatest range of styles and imagery of any object type from the Northwest Coast, their forms said to be the manifestation of the dreams and visions of shamans. The overall image of this exceptional amulet is that of an orca whale, indicated by the long dorsal fin extending back from the head. Two humanoid spirit figures are tightly interwoven with the whale image, the larger of the two situated just below the tip of the dorsal fin, while a smaller figure is positioned between the pectoral fins at the bottom of the amulet. Amulets are believed to contain the spirit power of the animal from which their source material was acquired. Sculpted from marine mammal ivory, this beautifully carved amulet would wield the power of the orca whale whose image is masterfully expressed. Deeply carved and brilliantly conceived to fit the narrow confines of a whale’s tooth, this amulet is the work of a master artist.

Before the end of the 19th century Yup’ik dance involved a great variety of masks, all of which were carved under the guidance of a shaman. The Nepcetaq is a rare mask said to rise and cling to the face of the shaman on its own accord (nepete means “to stick or adhere”). Unlike masks manifesting particular animal spirits, which were burnt or left to decay on the open tundra following the dances for which they were carved, Nepcetaq masks were owned by the shaman and kept over several ceremonial cycles. In the present example, small animal teeth set into the lips of the central face lend a bristling appearance to the grinning image. Four holes pierced through the flat rim might represent the passage and transformation between spirit and human forms. The faded painting and fragmentary remnants of feathers once looped by their quill tips through the small holes in the outer rim speak for the continued use of this expressive mask.

Atlatl is a word that comes from the Nahuatl or Aztec language and is also referred to as a throwing board. An ingenious and beautifully conceived piece of technology, the atlatl allows a hunter to pick up, mount, and let fly the hunting dart targeting seals and sea otters all with one hand, leaving the other free to steer the boat. The form is fashioned to fit the grip of one’s hand, effectively extending the hunter’s arm to increase the speed and flight distance of the dart arrows. The present atlatl is artfully formed and subtly decorated, and shows great age in its colouring and wear. Composed of harmonizing ridges and grooves, its form is very subtle and ambiguous, suggesting the snout and head of an otter-like animal, drawing upon the character and power of a respected predator.

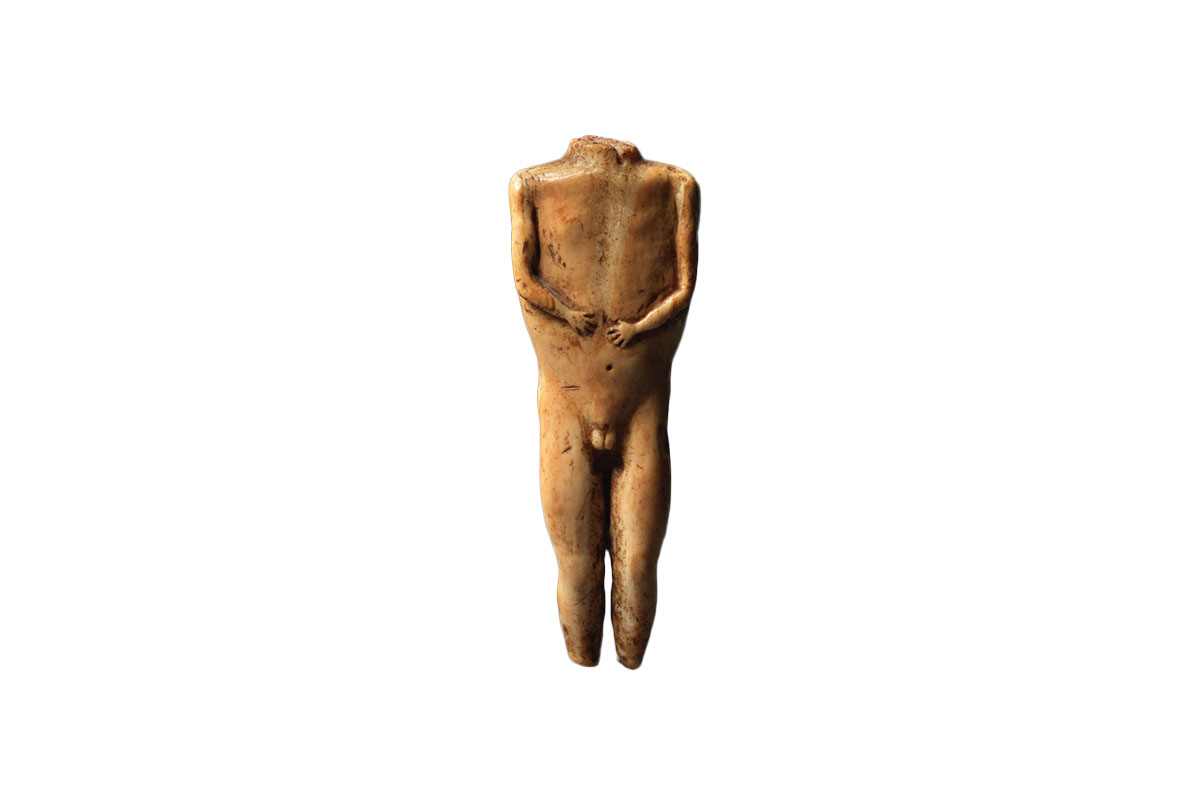

One of the earliest known cultural phases of the Bering Straight, objects stylistically identified as Old Bering Sea II (100 to 300 AD) principally emerge from the islands in Bering Strait and around the Chukotka Peninsula. This superbly carved torso is one of a small group of stylistically similar figures exhibiting thin arms and hands. Parallels can be drawn to the classic Okvik period (200 BC - 100 AD) figures of St. Lawrence Island, Alaska. In contrast to the highly abstracted human form found in Okvik art the surface is treated more plastically, with carefully defined muscle groups clearly distinguishing the chest from the arms, hips, upper and lower legs. The delicately carved hands are rendered in deep relief. This magnificent torso is widely perceived to be the finest extant example.

The two dolls illustrated here were likely commissioned sometime between 1890 and 1910 by Frederick W. Volz, an entrepreneur who acquired a trading post at Canyon Diablo, Arizona in 1886. The figures are notable for their large size, elongated torsos and tapered extremities. Another possibly unique feature of Volz dolls is the use of cloth for the kilts, sashes and other accoutrements, a detail commonly seen on Zuni carvings, as opposed to their painted representations on most other Hopi katsinam. By varying traditional designs with new interpretations, the Volz dolls illustrate the creative ingenuity with which Hopi artists protected the integrity of the katsina cult. Deviating from accurate representations of the katsinam, they represent the burgeoning of a flourishing artistic practice.

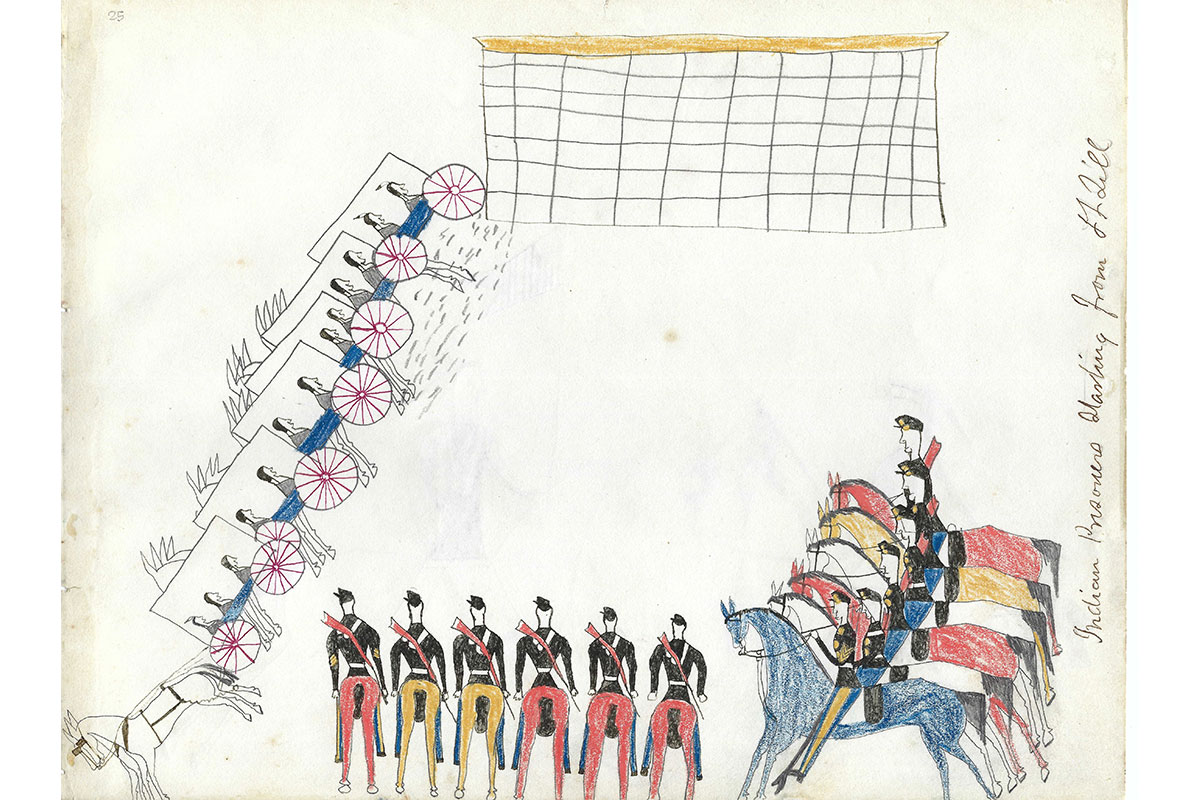

Although Ledger Drawings had occasionally been sold or traded with locally stationed members of the U.S. Army, a comprehensive commercialization of Ledger Art was fully realized with a group of exceptional drawings created between 1875-78 at Fort Marion, in St. Augustine, Florida. Provided with paper, crayon, watercolour and ink, approximately twenty-six Native American prisoners were encouraged to create drawings of their lives. In contrast to personal records of military feats which had dominated earlier Ledger Art, drawings from Fort Marion frequently depict memories of recent events, such as the prisoners standing from Ft. Sill depicted here. With these drawings, warriors such as Nokkoist (Bear's Heart, 1851-1882) showcased their artistic skills and made a small income from sales to the military men and local tourist community with whom they interacted on a daily basis.

The fifty-six drawings comprising the Cedar Tree Ledger Book are the result of a collaborative effort between five or six Native American artists from the Kiowa, Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne nations. Not much is known about Cedar Tree, the Southern Arapaho warrior artist to whom these two drawing are attributed. Around 1882, the year the Cedar Tree Ledger Book was first collected, he likely resided nearby the Cheyenne and Arapaho Agency in Darlington, Oklahoma. Cedar Tree’s autobiographical drawings describe a man of great accomplishment who possessed an extraordinary visual memory and demonstrated a remarkable attention to detail. The consistent depiction of himself holding a lance in his left hand along with the unusual left-to-right orientation of his drawings suggest that Cedar Tree was left-handed.