September 8 – October 21, 2021

A Visual Life Force

Historical Hopi and Zuni Katsina Dolls

"The katsinam, dressed in clothing covered with symbols of rain, corn and other features, are visual metaphors of life."

Emory Sekaquaptewa, distinguished Hopi leader and scholar

Donald Ellis Gallery is pleased to present A Visual Life Force: Historical Hopi and Zuni Katsina Dolls.

The exhibition showcases Hopi and Zuni katsina dolls carved in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Katsina dolls, which are known as tithu to the Hopi, are visual representations of the katsinam, the essential life force of all animate beings. Traditionally, tithu were gifted to children in order to familiarize them with katsina songs and dances. By the early 1930’s, propelled by a burgeoning tourist industry, workshops of artists produced carvings specifically for the non-Indigenous market.

The works in this exhibition present an important bridge between the beginning of a sculptural carving tradition and the flourishing curio trade. In the mid-19th century katsina dolls appeared as flat, board-like figures minimally painted with native pigments. By the end of the century, we see figures carved in the round, with distinctive torsos and legs and with more elaborate painting. By the 1890’s, facilitated by a partnership between the Santa Fe Railway and Fred Harvey companies, katsina dolls had become a new source of income for the Hopi and Zuni.

Although rarely acknowledged, the persistent impact of Hopi and Zuni katsina dolls stretches to the present day, from the Bauhaus to contemporary performance art, epitomizing the enduring legacy of Native American art on modern art and design. By showcasing these dolls we hope to highlight the immeasurable contributions that Hopi and Zuni carvers have made to Western art history.

The Katsinam

The katsinam embody the essential life forces of all animate beings. Residing in the six cardinal directions (northwest, southwest, southeast, northeast, zenith and nadir), they are largely beneficent and life-promoting. Personified by costumed dancers, the katsinam appear in Hopi villages, advising the community on moral conduct and admonishing those who have strayed from the right path. In the absence of a written record, the katsinam are the bearers of the community’s moral conscience. In return for the peoples’ sincerity of heart, they promise to adorn themselves with clouds and rain, descending over the plantations sheltered at the foot of the mesas.

The Volz Dolls

By the 1890’s, facilitated by a partnership between the Santa Fe Railway and Fred Harvey companies, katsina dolls had become a new source of income for the Hopi and Zuni. Frederick W. Volz was an entrepreneur who acquired a trading post at Canyon Diablo, Arizona in 1886. The six dolls illustrated here were likely commissioned by Volz for sale at his trading post sometime between 1890 and 1910. The katsinam are notable for their large size, elongated torsos and tapered extremities. Another possibly unique feature of Volz dolls is the use of cloth for the kilts, sashes and other accouterments, a detail commonly seen in Zuni dolls, as opposed to their painted representations on most other Hopi katsinam. By varying traditional designs with new interpretations, the Volz dolls illustrate the creative ingenuity with which Hopi artists protected the integrity of the katsina cult. Deviating from accurate representations of the katsinam, they represent the burgeoning of a flourishing artistic practice. Today, the majority of Volz dolls are in the permanent collections of major institutions, including the Heard Museum, Phoenix and the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington D.C.

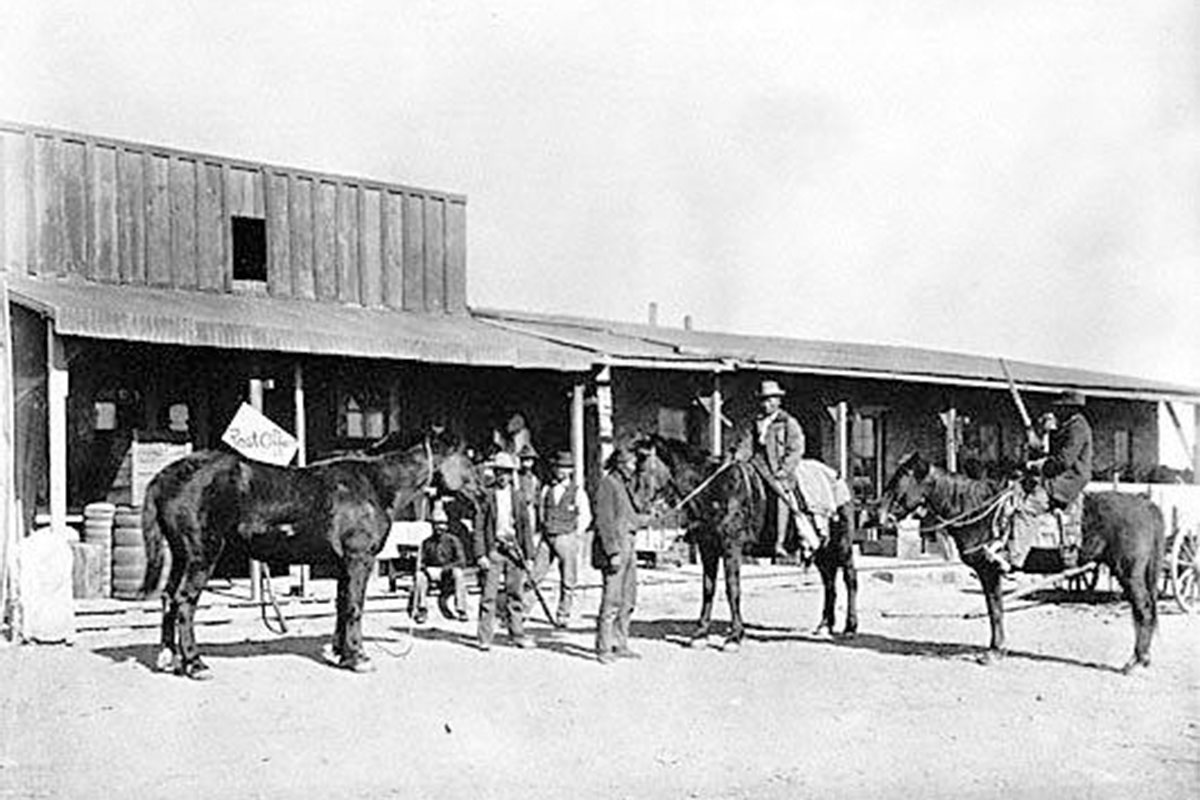

Frederick W. Volz's Trading Post in Canyon Diablo. Volz is standing fifth from left. © Cline Library Collection at Northern Arizona University

André Breton’s Apartment, 2003. © Estate of Gilles Ehrmann/SIAE, Pairs/VAGA, New York.

Katsina Dolls and Modern Art

Few forms of Native American art have had such an enduring impact on our imagination as the art of the American Southwest. The Pueblo cultures dispersed along adjacent portions of present-day Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah are some of the oldest continuously occupied communities in North America. For many European and American artists and intellectuals in the early decades of the 20th century, Puebloan art was of central importance to the development of the avant-garde. The image of katsinam appears across numerous artistic movements, from German Expressionist painting to Dada costume design of the early 20th century. Rejecting the notion of art for art’s sake, Surrealist artists like André Breton and Max Ernst were avid collectors of Native American art and frequently exhibited katsina dolls alongside their own works in a number of notable exhibitions. Common to all, katsina dolls represented the return to a form of art in which the creative was merged with the utilitarian, providing spiritual relief from the alienation of modern life.

Max Ernst among his collection of katsina dolls, 1942. © The Museum of Modern Art/Scala, Florence

"The down feathers worn on my head will be pleasing to you here.

Song of the Corn Boy Katsinam, recorded by Emory Sekaquaptewa

You, for your part,

when it begins to glisten with water along your planted fields,

along there you will go singing;

along there you will go expressing gladness."

Stylistic Development

Before the commercialization of katsina dolls in the early 20th century, katsina performers would gift small figures carved in their likeness to children. Unlike dolls in the Western sense, these figures were displayed on the walls of the family home in order to convey katsina songs and dances through storytelling. Katsina dolls developed from flat, board-like figures with barely differentiated heads and torsos. Most attention was paid to the painting of the mask, which is the most important characteristic of each katsina. Sometime in the late 19th century, more fully figured carvings with distinct torsos, arms and legs begin to appear. In contrast to the elaborate appearance of more recent dolls, the more powerful the katsina, the more abstract were its features. Carved from the roots of the cottonwood tree, much of their symbolism relates to water formations such as columns of parallel rain lines or stepped units of clouds.